The Author

Fay Bound Alberti

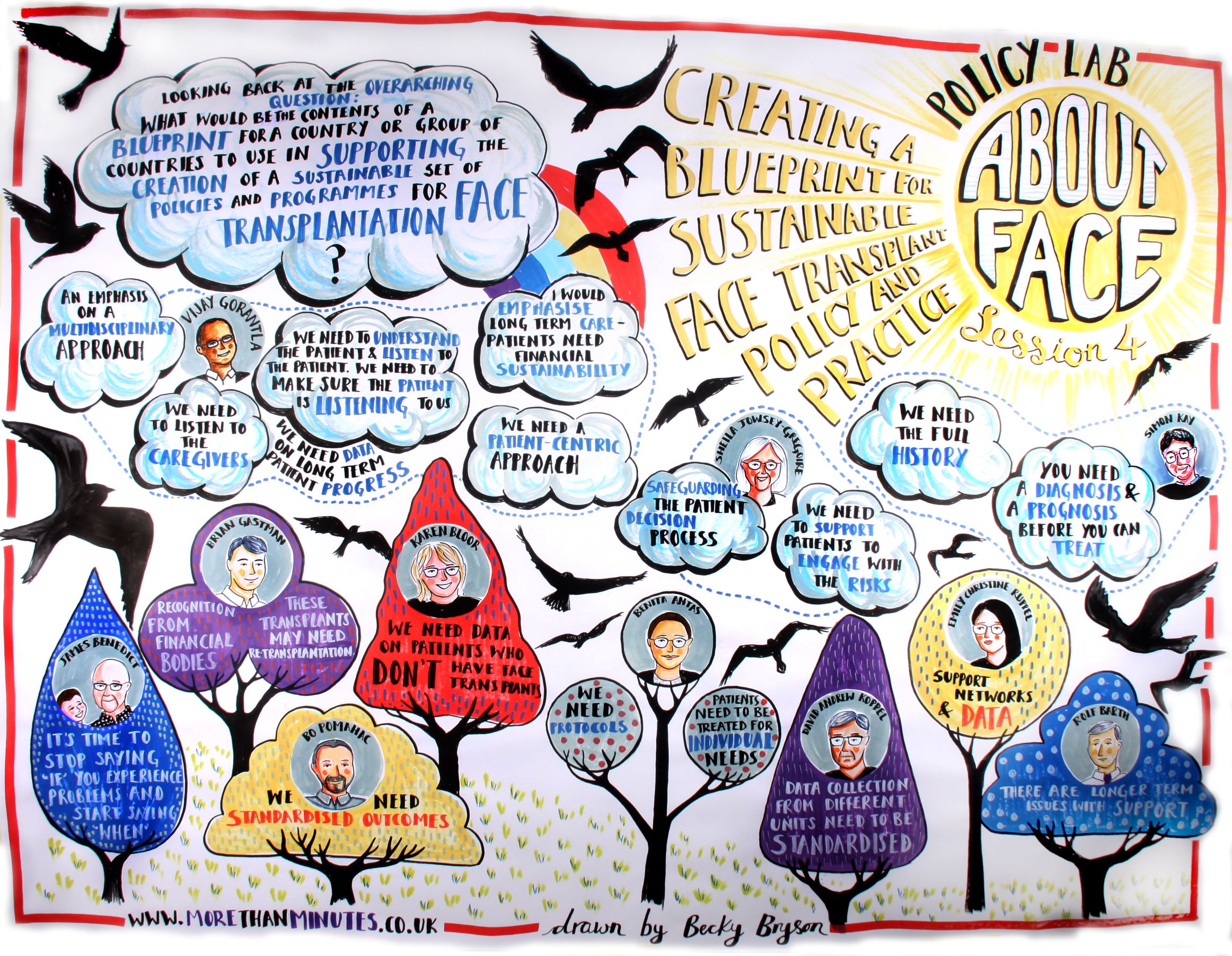

In December 2021, the AboutFace team convened a three-day Policy Lab with the support of the Policy Institute at King’s College London. The Policy Institute has a track record of bridging the gap between research, policy and practice, and making recommendations to UK policy makers. But the AboutFace policy lab was not looking to shape UK government policy around face transplants. Rather, its rationale was quite different.

The making of a blueprint. How historical, qualitative research should inform face transplant policy and practice.

One of the purposes of AboutFace research is to bring interdisciplinary, international expertise to bear on some of the pressing challenges around face transplants. I developed this programme of research into the history and ethics of face transplants because I wanted to ensure that all stakeholders were brought into the discussion: people with lived experience of visible difference, qualitative researchers, and extended surgical teams. The reasons why are quite simple.

Since 2005, when the first face (partial) face transplant took place, the emphasis has shifted in ethical debate from whether it could or should happen to how it happens. Yet many of the issues raised in 2003 and 2006 by the Royal College of Surgeons are still problematic. Heavy use of immunosuppressants carry a health burden for the whole patient and are life-reducing. The estimated length that a face transplant will survive is ten years, though there are some exceptions. There is no consensus on how patients should be selected, and no real data sharing across boundaries. There is not even any agreement on what success looks like in face transplants, a subject I am talking about at the International Society for Vascularized Composite Allograft conference in Cancun this week.

Creating a Gold Standard

In bringing experts from all around the world together, we wanted to create a blueprint that makes recommendations for best practice; a gold standard in how far transplant policy and practice should be led. We were heartened by the consensus in the room, and by the simplicity – but importance – of the recommendations being made to surgical teams to ensure patients receive the best possible treatment.

We believe that this Blueprint is also an example of how qualitative, historically-informed research can help shape and inform surgical practice, and make an international impact. We have included sections on patient selections and expectations, clinical frameworks, patient support networks, public image and perception, financial sustainability and data on patient outcomes and progress.

While this report has a surgical focus, because we are reaching out to extended surgical teams and nurses around the world, we will also be working to engage patients and their families with our findings. We will be releasing a series of videos and discussion points over the coming months. In the meantime, we invite you to read the report and let us know what you think. Any questions, ideas or concerns, get in touch with us.