The Author

Dr Lauren Stephenson

This piece on transplantation and The Eye (2008) is the second blog in our series on Halloween, Horror Films, transplantation and the face. In this installment, Lauren Stephenson (York St John) explores the tensions between science and the body, and matters of the soul and the self. Catch up with the other blogs in the series, by Fay Bound Alberti, Sara Wasson and Paddy Adamson. Our final blog in the series, by Paddy Adamson, will be released next week

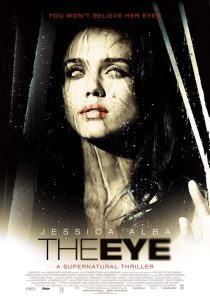

‘Like Changing a Windshield on a Car’ – Transplantation and The Eye (2008)

The Eye (2008) is a U.S. remake of the earlier Pang Brothers film Jian Gui, released in 2002, which arrived in theatres as the Hollywood penchant for adapting successful (and sometimes notorious) East Asian horror films reached its zenith. As such, it is perhaps most often discussed as part of a debate regarding remake culture in the U.S., within which fans and scholars alike tend to become combative over the superiority of the original texts, and uninhibited in expressing their disappointment with their often cynically marketed remakes.

What becomes lost or minimised during this debate, however, is how both films (original and remake) attempt to re-examine our relationship with our corporeal selves, passing commentary on the ethics of transplantation by focusing not on the procedure itself, but rather the protracted process of adjustment and recovery which follows it. For the purposes of this piece, I’ll be focusing in particular on the U.S. remake of this transplantation narrative, which reveals an ambivalent stance towards medical procedure, but demonstrates tangible anxiety regarding notions of selfhood and identity after transplantation has occurred.

A ‘haunted organ’

The film begins by introducing us to our protagonist, Sydney (Jessica Alba). Sydney has been without sight since she was 5 years old, when an accident with fireworks damaged her eyes. In the opening moments of the film, Sydney monologues about her desire for sight and vision; a musician by profession, Sydney comments; ‘I bet music looks beautiful’ – an interesting comment which seems to suggest that even predominantly auditory experiences are, for Sydney, incomplete without her sight (an ableist narrative which is equal parts challenged and reinforced throughout the unfolding film).

This desire to regain her sight and restore a ‘complete’ experience leads Sydney to attempt a bilateral cornea transplant (the representational accuracy of which is questionable). We learn later that this isn’t the first time she’s undergone the procedure, with her first transplant corneas rejecting during a procedure when she was 12 years old. Following a successful second attempt, the film begins to shift consistently between a conventional third person perspective and Sydney’s first-hand POV, hypothetically placing the audience in the position of a recovering cornea transplant patient. Sydney’s vision is, to begin with, blurred, and it is here where the film’s central conceit – that of the ‘haunted organ’ – begins to exploit the recovering organ and patient as facilitators for horrific ambiguity. Sydney, and by extension the audience, begin to witness blurry figures and unexplainable visions; it quickly becomes clear that Sydney’s eyes have not only given her sight in the conventional sense, but have left her with the ability to see what others can’t: the dead.

Recovery

Sydney’s status as a recovering transplant patient means that her authentic experiences of her new eyes are readily dismissed as hallucination or a failure to adjust post-op. Medical professionals are conspicuously absent from the narrative, with the most consistent representative of the medical field being a Dr Faulkner (Alessandro Nivola), a post-transplant specialist whose behaviour throughout the film vacillates between gaslighting and romantic interest. As Sydney’s sight improves, so too do her supernatural visions become more vivid. Seeking help from Dr. Faulkner, his troubling and flippant response seems to suggest that Sydney’s vision are not only imagined, but a device to maintain her sense of self as ‘special’ following her op:

Faulkner: ‘You just discovered that you’re like the rest of us’

Sydney: ‘You know, when we first met, I didn’t think you were such an ass’

Faulkner: ‘That’s ‘cos you didn’t know how to spot one. See? Progress.’

Denying Subjectivity

The reframing of Sydney’s ongoing trauma as something self-inflicted and self-interested poses an interesting ethical question; Faulkner’s response denies Sydney subjectivity, autonomy and respect in her recovery, delineating her instead as a gothic heroine and hysterical woman (Showalter, 2000: 190). In framing Sydney’s narrative within the confines of transplantation, and with a fixity on eyes and vision, the film makes explicit the conventional use of the unreliable narrator; Sydney’s recovering vision means that what she witnesses can easily be derided or explained away.

The donor’s eyes thereby become a narrative metaphor for the routine marginalisation of women’s voices and experiences. The donor’s death, we learn later, was at the hands of her community who failed to heed her supernatural warnings of an imminent factory fire, later blaming her for the incident once lives had been lost. When these become Sydney’s eyes, the shared vision of donor and recipient combines to present a reasonably compelling account of the systemic dismissal of women’s accounts and experiences. However, this allegory comes at the expense of dramatising and exploiting the very real disorientation, dissociation and loss of selfhood associated with transplant recovery.

An ‘ideal’ horror heroine

With this in mind, despite the ways in which the film draws upon established conventions of the ghost and the body to create its impact, some of the most unsettling moments within the film come not from scenes of overt horror (though there are several) but from the way in which Sydney, her regained sight and her recovery are treated by her friends, her doctors and colleagues in the first act of the film. In one early scene, Sydney returns to her home post-surgery, only to find it filled with family and friends, hosting her a ‘surprise’ welcome home party. As faces, some of which she’s never seen before, swim before her, we experience a sense of overwhelming claustrophobia – an experience which eventually drives Sydney to retreat into the kitchen, away from the crowds.

In another instance, Sydney’s conductor becomes noticeably agitated and frustrated when it appears she cannot immediately adjust to playing her violin sighted after the operation. It would appear that the timeline for Sydney’s recovery, and indeed the way she processes that recovery, is consistently framed within the expectations of others. Her recovery is either not fast enough, not full enough, or not simple enough, to sustain investment from any of the other principal characters within the film, and this creates an isolation that sustains her as an ‘ideal’ horror heroine.

The Body and the Self

Later in the film, Sydney is shown a photo by her sister, and realises that the woman she is seeing in the mirror isn’t her (this recalls a moment in her opening monologue, where she comments that she doubts she will even recognise herself once her sight is restored). The woman Sydney sees in the mirror is in fact her donor, and the dissociation this speaks to, however clumsily, seems to demonstrate some fear or anxiety surrounding the nature of the body itself, and its relationship with the person, soul or being that inhabits it. This is particularly pronounced in that the organ here is the eye; the ‘window to the soul’.

Notions of ownership and selfhood are explicitly challenged here; Sydney’s eyes work in tandem with her body, yet they show her images, visions and events past and present, not all of which belong to her, and none of which she has control over. Indeed, in the final act of the film, Sydney embraces her role as a kind of ‘custodian’ of her donor’s eyes, allowing to be guided by the premonition she has been seeing in excerpts throughout the film. She saves countless lives in doing so (thereby inferring that this was the correct and heroic thing to do) but also sacrifices her sight once again to ensure the safety of others.

Sacrificial Heroine

In the end, the supernatural and a pseudo-religious belief in the soul and afterlife trump science in The Eye. Unlike many ‘surgical horrors’, which characterise science as ‘the deus ex machina, promising to restore limbs and faces that have been irremediably lost’ (Aldana-Reyes 2014: 147), The Eye, and Sydney as its protagonist, regard science as a means through which to restore something less tangible – Sydney’s relationship with her donor eyes restores justice and peace to her donor and delivers dozens of people from death at the hands of a freak accident.

In its complicated relationship with the ethics and responsibilities of the transplant industry, the film eventually side-lines a consideration of transplantation itself in favour of casting Sydney as saccharine sacrificial heroine; one whose relationship to her new eyes is happily relinquished in the interest of saving others.

That the final scene of the film imagines Sydney as more complete and fulfilled without her donor eyes than with them speaks volumes; transplantation here is seen as a means to a narrative end – in The Eye, matters of science and the body are no match for matters of the soul and self.

Works cited:

Jian Gui (dir. Pang Brothers, 2002)

The Eye (dir. David Moreau & Xavier Palud, 2008)

Reyes, X.A. (2014). Body Gothic: Corporeal Transgression in Contemporary Literature and Horror

Film. (Cardiff: University of Wales Press).

Showalter, E. (2000) ‘Dr. Jekyll’s Closet’ in Ken Gelder (ed.). The Horror Reader. (London: Routledge).

p.190.

Author Bio

Lauren Stephenson is Senior Lecturer in Film and Media & Communications at York St. John University, U.K., where she teaches across the fields of Film, Media, Literature and American Studies. Her research interests include Horror cinema (in particular, British, American and New Zealand Horror), Gender and Horror, and women’s friendship in cinema. She is the co-founder of the Cinema and Social Justice project at YSJ (@cinemajustice) and has most recently written on folk horror, the Fear Street series and its adaptations, and First Ladies in U.S. disaster movies. Follow her on Twitter at @laurenrachel11.