The Author

Emily Cock

For Face Equality Week 2021, Emily Cock writes about encountering facial difference in historical documents, and the associated emotional and ethical issues.

History has Many Faces: researching histories of facial surgery

This is a post about the conditions in which I am able to research facial difference in early modern history. It is a post about the ways in which book provenance and the building of research collections tie sixteenth-century facial surgery and medicine to the more recent past, and to contemporary ethical issues faced by libraries, archives, and the people who use them. Ultimately, it is a post about the historical research and book collection of physician Ernst Alfred Seckendorf, who was born in Nuremberg on 30 December 1892, and murdered in Auschwitz concentration camp on 11 February 1943.

Dr Seckendorf occupies a small note in a spreadsheet I constructed for my book on early modern rhinoplasty. I was recently reminded of this note while listening to one of the Folger Library’s brilliant 2020-2021 Critical Race Conversations talks. The conversation was a rich discussion between Urvashi Chakravarty and Brandi K. Adams on Race and the Archive. Please do check it out soon.

Adams and Chakravarty cover a lot of ground in the session, but I was particularly struck by their notes on the role of white supremacy in constructing and regulating access to archives. The presence of Seckendorf in my notes on sixteenth-century Italian facial surgery is an illustrative point that all research collections can prove this true, and that efforts to shed light on the stories of one discriminated-against minority can be contingent on the exploitation, subjugation, or even annihilation of another.

Seckendorf and sixteenth-century facial surgery

Seckendorf was a former owner of Chicago Northwestern University’s copy of a pirated edition of Gaspare Tagliacozzi’s De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem (1597; this edition was printed in Frankfurt in 1598 as Cheirurgia nova). As I began to research the provenance of copies of Tagliacozzi’s book during my PhD, I emailed libraries around the world for information on their holdings. I regret that Northwestern’s correspondence was lost with the end of my email account for that university, so I cannot name and thank the librarian who helped me at that institution (I have learned from this mistake in my practice, and now always try to acknowledge this labour!).

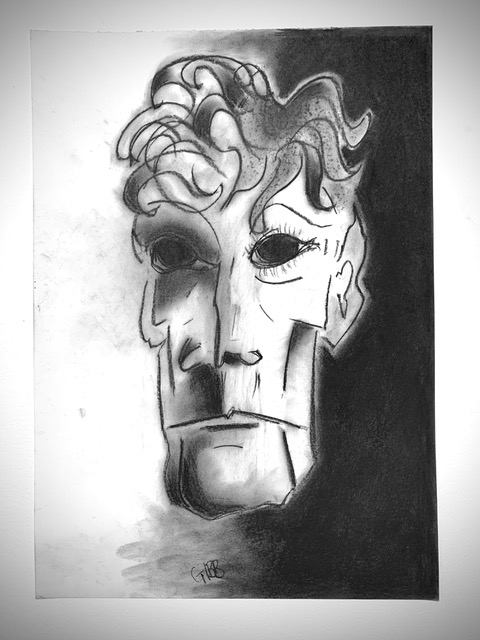

In this book, the Bolognese surgeon Tagliacozzi (1545–1599) detailed how a skinflap from the arm could be used to reconstruct a nose, lip or ear. Surgeons would continue to use this skinflap technology into the twentieth century: Sir Harold Delf Gillies (1882–1960), who led the immense developments in plastic surgery in WWI, conceded that the ‘There is hardly an operation – hardly a single flap – in use to-day that has not been suggested a hundred years ago.’ Tracing copies of Tagliacozzi’s and related books helped me to explore the circulation and reception of these ideas in the intervening centuries, and thus levels of access to facial surgery techniques for people with significant facial difference from injury, illness, or other causes.

According to the city’s Wiki, Seckendorf practiced in the Bavarian town of Fürth from 1921, specialising in skin, urinary and venereal diseases. He had an interest in medical history, which extended to translation of Latin texts: his German translation of Italian physician Girolamo Fracastoro’s (c. 1476/8-1553) Syphilis sive morbus gallicus (1530) was first published in 1960. This was the first text to use ‘syphilis’ for a disease that plagued early modern Europe, accruing many pejorative and often xenophobic names. I am grateful to Sara Belingheri at the closed Wellcome Library for providing an ad hoc scan of the book’s biographical notes on Seckendorf and Fracastoro by German dermatologist and medical historian Walther Schönfeld (1888–1977).

How research collections are formed

Last year, AboutFace hosted a workshop and published a series of posts about the emotional and ethical dimensions of researching and publishing medical images of the face. The contributors raised important issues about the invasion of the photographed person’s privacy, acknowledging and negotiating the emotional effects of these images on the researcher, and using difficult images in teaching, among other topics. But my contribution today perhaps shares the most ground with Michaela Clark’s call to heed the tactile and material when thinking about the photographs and other sources that researchers use to understand historical experiences and ideas of facial difference. In the case of Seckendorf’s copy of Tagliacozzi in an American university library, what conditions have contributed to the construction of archives and public availability of research materials?

Seckendorf tried to leave Germany in 1937 but was denied. He is still listed in a 1937 medical directory as a “Jewish specialist for skin and venereal diseases” (in Schönfeld, 19). He was arrested in January 1938, officially for performing abortions and for attempting to marry a non-Jewish German woman. Most online portraits of Seckendorf are the photographs used by the police after his arrest, and in the Nazi media when targeting him just prior (see the news clipping on the general German Wiki). It was therefore striking to see an alternative, personal photo used on the Fürth Wiki page. These photographs are, after all, a new archive through which the public understanding of Seckendorf is to be built up, and the choice of image a very deliberate and consequential move.

There are provenance notes inside the copy of De curtorum chirurgia that can be used to trace some of its sale history. At one point, publisher J.F. Lehmann sold the book in Munich. Someone purchased the book from the still-extant Munich Karl & Faber auction house in 1932. One of these purchases, or possibly even the selling of the book, might have been by Seckendorf. I do not know the circumstances behind Northwestern University Library’s acquisition of this book. Perhaps the prominence of Seckendorf’s bookplate at least indicates a disinterest in denying or destroying the book’s provenance by whoever sold it to the library.

But millions of books were stolen from Jewish owners, including on Jewish topics, with restitution a slow process that receives less attention and funding than for more glamourous objects like priceless art. Schönfeld says that Seckendorf had an extensive (‘umfangreiche’) library of medical literature and history. Further research by people more skilled in twentieth-century German book history than myself will be required to establish the full circumstances of his collection’s dispersal.

Provenance as ethical practice

I do not know enough about Seckendorf’s practice to explain the specific information he might have gleaned from De curtorum chirurgia, but it intersected with his specialisations in the skin and venereal diseases, since destruction of the nose was strongly associated with syphilis. He published a number of articles on medical history and on current practice. I argue in my book that some surgeons in controversial fields like plastic surgery used history and bibliography to defend their practice: operations to reshape the nose, for example, were not just products of ‘modern’ vanity, but had histories of development to help men injured in wars, duels, and other honourable, masculine pursuits. Perhaps Seckendorf saw similar value in contributing to the historical understanding of venereal and skin diseases.

Tracing books by previous owner is a difficult process: provenance information is often held in libraries’ private or less-searchable catalogue metadata, assuming that they have had any budget to research and catalogue this information to begin with. Nevertheless, I hope that it is only a matter of time before Seckendorf’s library can be reconstructed, if only as a digital catalogue, and his contributions to medical history better appreciated.

In the meantime, Seckendorf’s copy of De curtorum chirurgia, and Adams and Chakravarty’s discussion, remind us of the many historical figures, structures and processes entwined around the research materials that we can sometimes take for granted.

Author Bio

Emily Cock is a Lecturer in Early Modern History at Cardiff University, and author of Rhinoplasty and the nose in early modern British medicine and culture (Manchester University Press, 2019). Emily’s research explores early modern social and cultural histories of medicine, sexuality, and disability.